Milner repeatedly ran into the issue that the theorem provers would attempt to claim a proof was valid by putting non-proofs together.[10] As a result, he went on to develop the meta language for his Logic for Computable Functions, a language that would only allow the writer to construct valid proofs with its polymorphic type system.

The LCF page says

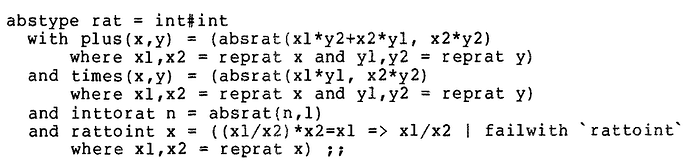

Theorems in the system are terms of a special “theorem” abstract data type. The general mechanism of abstract data types of ML ensures that theorems are derived using only the inference rules given by the operations of the theorem abstract type. Users can write arbitrarily complex ML programs to compute theorems; the validity of theorems does not depend on the complexity of such programs, but follows from the soundness of the abstract data type implementation and the correctness of the ML compiler.

Is this literally true? Can we actually encode logics in the ML type system so that the ML type system is itself enough to guarantee that the rules of the logic are followed? It seems a little implausible to me that the ML type system on its own is enough to guarantee the correctness of a proof.

The modern ML module system wasn’t developed until like a decade later, so I don’t even know if they are referring to the use of signatures here. Is there a simple architecture that sketches the use of this?